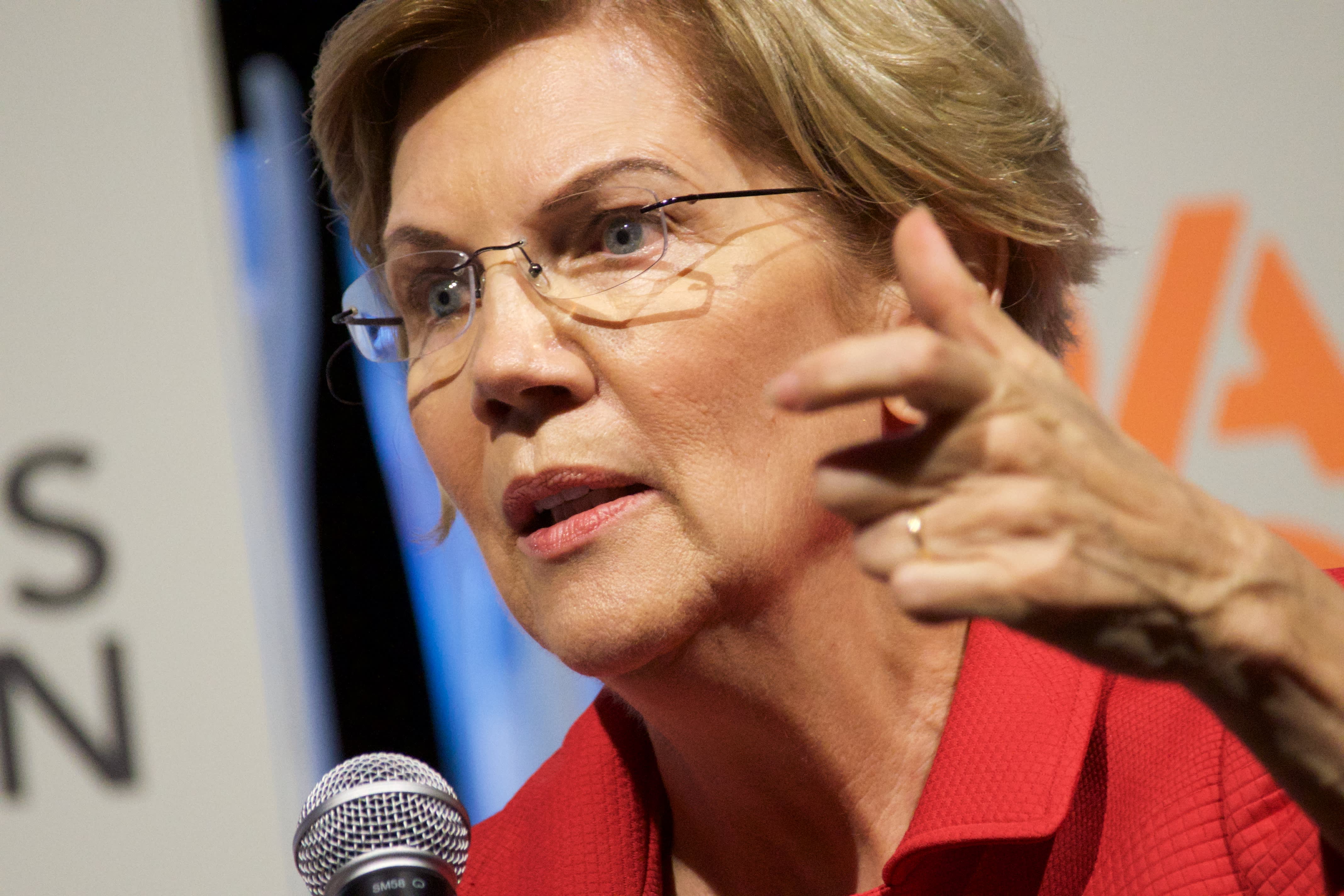

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, as well as three other Democratic Presidential hopefuls Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, Gov. Jay Inslee and react to questions during the Daily Kos/Netroots Nation candidate forum, at the Convention Center in Philadelphia, PA, on July 13, 2019.

Bastiaan Slabbers | NurPhoto | Getty Images

A new study from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School finds that Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s proposed wealth tax on the richest Americans will generate at least $1 trillion less than what the campaign claims, potentially undermining the key funding source for her plans to expand government-backed health care, education and other programs.

Warren’s tax, if implemented in 2021, would raise between $2.3 trillion and $2.7 trillion in additional revenue over 10 years, well below the $3.75 trillion her campaign estimates, according to the university’s report viewed by CNBC.

In other words, Wharton projects the proposed wealth tax will raise $1 trillion to $1.4 trillion less than the Warren campaign advertises.

“That does mean — to the extent that they’re thinking about this money being used to pay for spending priorities and things like that — they will need to figure out how to come up with that difference,” Kent Smetters, faculty director for the Penn Wharton Budget Model, said in an interview with CNBC.

The Wharton report also said that the proposed tax would result in secondary economic impacts for families not directly subject to the duty.

Its findings indicate average hourly wages in the economy, including wages earned by households not directly subject to the wealth tax, are projected to fall between 0.8% to 2.3% due to the reduction in private capital formation.

It also says the tax would shrink the U.S. economy between 0.9% and 2.1% by 2050 depending on how Congress spends the revenues.

“There’s a fundamental trade-off between how much money you raise and the impact it’s going to have on the economy,” Smetters said. “A wealth tax doesn’t just affect the billionaires: It has a broader impact on everybody because those billionaires are investing in companies that employ everybody.”

“They’re not just employing other billionaires,” he added.

The Massachusetts Democrat and 2020 presidential hopeful unveiled the latest iteration of her proposal last month, when she announced a doubling of her billionaire tax from 3% to 6%. Warren’s wealth tax would also impose a 2% tax on net worth between $50 million and $1 billion and scale upward by wealth brackets until the final 6% rate.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) addresses a rally against the Republican tax plan outside the U.S. Capitol November 1, 2017 in Washington, DC.

Getty Images

The campaign, which has relied on research from economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, estimated that doubling the highest rate would raise an additional $1 trillion over 10 years on top of her original wealth tax.

All told, the combined figure could be north of $3.5 trillion over 10 years, according to the Warren campaign. But that’s well above what the Wharton study expects.

‘Unsupportable assumptions’

Before including the tax’s macroeconomic effects on wages, hours worked and GDP growth, the university expects the tax to generate $2.7 trillion in real dollars. Accounting for such ripple effects yields the lower, $2.3 trillion projection.

The Wharton figures, if correct, would represent a marked shortfall for the Warren campaign, which has billed its wealth tax as integral to its campaign ambitions for proposals like “Medicare for All” and reducing student loan debt.

The Warren campaign, however, staunchly defended the wealth tax in an email to CNBC and argued that the Wharton study incorporates indefensible assumptions.

“This analysis does not study Elizabeth’s actual plans — it does not account for the strong anti-evasion measures in her wealth tax and does not even attempt to analyze the specific investments Elizabeth is committed to making with the wealth tax revenue,” Saloni Sharma, the Warren campaign’s deputy press secretary, told CNBC.

Critiques of the Wharton analysis could include its failure to consider the senator’s anti-evasion measures, designed to prevent households from reallocating cash to minimize or circumvent the tax.

The Wharton authors acknowledge this in their study, noting that in the absence of specific legislative language, their evasion estimates are an educated guess based on the international record with wealth taxes.

They also concede that the Warren campaign “stresses that significant enforcement efforts will be enacted as part of the policy,” including an acceleration in IRS audit rates.

The study admits it doesn’t account for the types of investments that could be made using the wealth tax’s revenues when determining the growth effects of her plan.

Should Congress use the revenue in a way that makes American corporations more productive (through fewer employee sick days or a better-educated labor force, for example), the adverse impact on economic growth would at least be lessened.

“This is an analysis of a different and worse plan than Elizabeth’s, using unsupportable assumptions about how the economy works, and its conclusions are meaningless,” Sharma added. Other experts and economists have found “that her middle-class investments will produce significant economic growth.”